Son of a Bootlegger

The story of South Carolina's second-ever All-American and the outlaw who sired him.

When Bryant Meeks leapt from his still-moving Ford sedan, there were five gallons of whisky in the back seat. A pair of federal agents had spotted Meeks a few miles outside of Macon and began following him across a bridge spanning the Ocmulgee River, into the heart of the city. Once they were downtown, Meeks’s accomplice in the passenger seat — who, unlike Meeks, managed to escape — was the first to bail on the vehicle. Meeks, now alone in the car, turned left onto Orange Street, four blocks from the campus of Mercer University. As his pursuers began to overtake him, Meeks concluded that his only hope of evading arrest was to exit the vehicle. So he jumped from the moving car, which then veered off the road and crashed into the edifice of the private residence at 271 Orange.

When the officers exited their car to begin the foot pursuit, they already knew Meeks for a veteran scammer and convict, who flitted from one illegal scheme to the next, stopping only for the occasional stint in prison. But even incarceration didn’t always prove a sufficient impediment to Meeks’s law-breaking; in 1928, he escaped a chain gang in Butts County — to which he was sentenced for his role in a string of chicken thefts — and successfully evaded capture for three years. Shortly after his release, Bryant was sentenced to probation for violation of federal prohibition laws. He was then jailed in April 1931 for violating the terms of his parole. Namely, he was found to be operating a liquor business out of his home, the supplies for which, investigators concluded, had been driven in from a booze-smuggling ring in Florida.

Bryant made his debut in the criminal justice system at the age of 22, when he was picked up for stealing $50 worth of meat from an elderly widow. From the ages of 23 to 29, Bryant stayed on the right side of the law — or at least, his absence from arrest records suggests that, for six years, police did not directly observe him while he was on the wrong side of the law. But not long after Meeks and his wife welcomed their first son into the world, the pressures of fatherhood got to him. It was then that Bryant and an accomplice cooked up the idea for stealing chickens. They’d rip off local farmers in Jackson, then head in to Atlanta and Macon to sell their stolen livestock to unsuspecting customers.

But in the final years of the federal government’s ban on the production, transportation, and consumption of alcohol, Bryant Meeks was also settling in to the scam that would define the rest of his criminal career: bootlegging, with a specialization in moving booze from Florida to Georgia to circumvent taxes and stricter prohibition laws in the Peach State. From 1931 to 1961, police arrested Meeks at least nine times for violating liquor laws, with a gambling bust thrown in for good measure. His last big job came at the age of 67, when FBI agents busted him for conspiring with a suspended police officer to steal the trailer of a shipping truck, and the $20,000 worth of whisky contained therein.

To our 21st-century sense of morality, some of Meeks’s behavior might scan as more self-destructive and sinful than malicious and criminal. But that’s not to say his actions were without victims. For at home there was a Mrs. Meeks, born Lola Alderman on a farm outside of Tampa. Lola was just 16 when she made the decision that would shape the trajectory of her adult life. To the extent that a girl in the year 1924 getting married at the age of 16 can be said to have been making a decision. (But Lola might have grown up expecting a fate such as this, having seen her older sister, Lizzie, married off at 14.)

A year into her marriage to Bryant Meeks, Lola learned that she was pregnant. In 1926, she gave birth to a son, who she gave his father’s name. But, until two decades later, around the time the Pittsburgh Steelers selected him in the NFL Draft, the baby was known simply as “Junior.”

From 1932 to 1937, Lola Meeks sued her husband for divorce on three separate occasions. In the first divorce — finalized in 1933, during one of Bryant’s prison sentences — Lola charged him with “cruel treatment and habitual intoxication,” adding that he had been a “confirmed bootlegger” for the past five years. But Lola and Bryant remarried two months later, while he was out on parole. Lola filed a second petition in 1934 but eventually dropped it. The one that stuck came three years later, in 1937, two months after Junior went to the hospital to receive treatment for a scalp laceration.

Doctors were told that the 11-year-old had accidentally head-butted a brick wall.

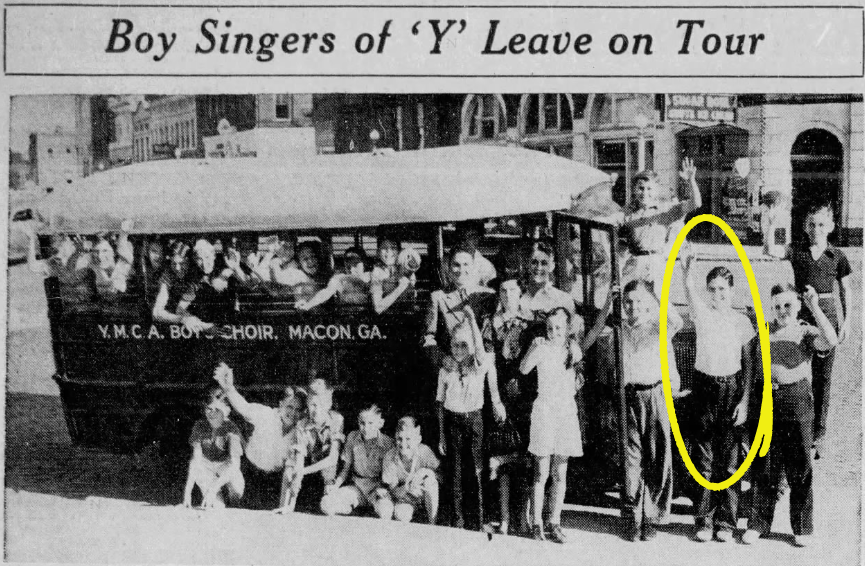

It was around the time that Lola banished Bryant for good that Junior became a fixture at the local YMCA. The Macon Y was just about eight minutes by bike from their house on 2nd Street. There, Junior competed in just about every athletic competition imaginable: broad jump, gymnastics, backward running, "indoor baseball throw," and swimming and diving. Junior also sang in and traveled with the YMCA choir. In 1938, the choir boarded a bus for Washington, D.C., where they performed at the church of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Given the timing, it’s hard to wonder if Junior’s involvement at the Y didn’t come at the express direction of his mother. Perhaps she thought the structure, exercise, and fraternity on offer would fill a void left by his father. Perhaps she thought this would help set Junior on a path very different from the man whose name he shared. Whatever the motivation and whatever role the YMCA did or did not play, one thing is clear: Junior Meeks could not have been more unlike his father if he tried.

Of course, maybe he was trying.

At the age of 14, Junior had his first and only known run-in with the law: Judge George Nottingham sentenced Meeks to 60 days of walking, as punishment for violating a city ordinance against riding bikes on the sidewalk. The terms of his sentence lengthened Junior’s commute to the YMCA by 22 minutes.

Not deterred, Meeks graduated from field day sports to YMCA-sponsored baseball, basketball, and football teams, competing for city championships with each. By 15, he was promoted to the varsity football team at Lanier High School, and at 16 he became a starter on both offensive and defensive line. At 17, he enrolled at the University of Georgia on a football scholarship and walked straight into the starting lineup as a true freshman.

An ROTC student in high school and college, Meeks enrolled in the V-12 program, started in 1943 to meet the excess demand for naval officers created by World War II. V-12 took Meeks back home, to Mercer University, a few minutes’ walk from the terminus of Bryant Sr.’s high-speed chase with federal prohibition officers. During his year in Macon, Junior starred on the Mercer University softball team (for whom he was the ace pitcher) and the basketball team (leading the Bears to a big win over UGA hoops for whom he’d played the year prior).

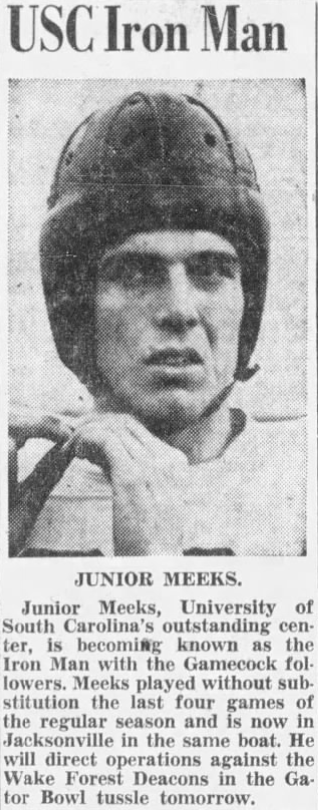

That summer, V-12 required Meeks to relocate once more. This time, he was off to Columbia, South Carolina, where he immediately became one of the Gamecocks’ most important football players. Though Meeks was a two-way star — as the rules at the time basically required — he made his hay on offense, as a center. Meeks was prized for his ability to accurately snap the ball, and his lithe 6’2, 185-pound frame allowed him to quickly pull down the line. Meeks led USC to the Gator Bowl as a junior and, as a senior, collected second-team All-America honors from the Associated Press.

The summer before his senior year, Meeks received his commission as an ensign in the naval reserve. Two months later, he married his high school sweetheart, Jacqueline Griffis, to whom he remained married until her death in 2002. The wedding announcement in the Macon Telegraph makes no mention of Bryant Sr. or his new wife, Annie, who was just seven years older than Junior. It does note that the ceremony was held “at the home of the groom’s parents” but, curiously, ascribes to them names we have not yet encountered in this tale: “Mr. and Mrs. W.P. Wilson of Macon.”

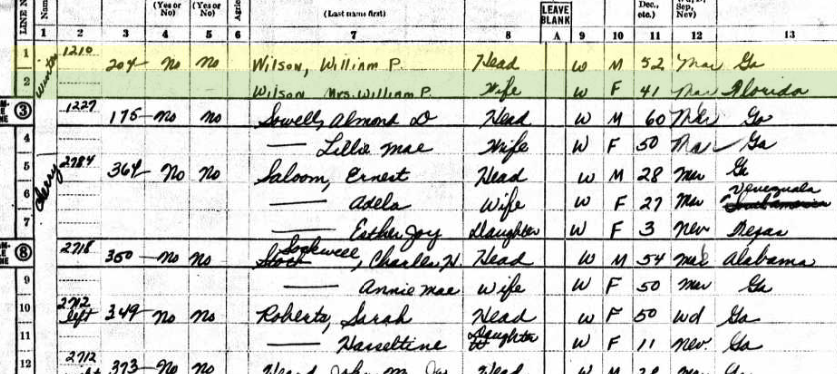

On April 16, 1950, Kathryn Bradley walked up the brick steps leading to the front porch of 1210 Winton Avenue in Macon. She was there to make sure the residents of the 1,800-square-foot house on the corner lot were counted in the 1950 census. After knocking on the door, she spoke to William P. Wilson, who described himself as the 52-year-old head-of-household and a proprietor of a local restaurant. The restaurant is likely an establishment called Wilson’s Restaurant, a popular meeting place on Cherry Street, just two blocks away from where Lola Meeks once lived with her two sons. Wilson also provided biographical details for his wife, who he described as a 41-year-old woman born in Florida — details that were also true for Lola Meeks.

The name that Bradley recorded for William P. Wilson’s wife was not her actual name, but only “Mrs. William P. Wilson.” This is not how Bradley would have been trained to record Mrs. Wilson’s name; as you can see from the other entries, the first and last name is taken for every member of the household — even children and renters. This oddity is likely connected to the fact that part of the entries for 1210 Winton appear to be written by someone other than Kathryn Bradley. On every other entry in the 81 log sheets Bradley completed for the 1950 census, she wrote in a neat cursive. But here, the names were written in print. And of the 20 columns devoted to the residents of 1210 Winton, only the name column is written in this hand.

The entry does not appear to have initially been written in another hand, only to have been crossed out and written over at some later point. Did someone at the doorstep wrest the ledger from the census-taker’s hand and write it themselves? Why might they have done this? With all of the witnesses to this doorstop conversation now long-deceased, we can only speculate about what might have happened. But there are some possibilities that would partly explain both the marriage announcement and the census record taken four years later.

The first possibility is that Leona did not want her name printed in the newspaper because she hoped to conceal her location from her ex-husband. So fearful was she, not even the 72 years of confidentiality guaranteed by the census could put her at ease.

Another possibility: W.P. Wilson was equally loath to reveal the true nature of his relationship to Lola Meeks. Wilson, it seems, was concurrently married to another woman, Myrtle Weatherly. When Weatherly answered the door for the 1950 census-taker, she was living 80 miles away, with her and W.P. Wilson’s son, Fred.

Further complicating matters, records show that Lola Meeks was granted an uncontested divorce from W.P. Wilson in 1946. And yet she was apparently still cohabitating with W.P Wilson and representing herself as his wife as late as 1950.

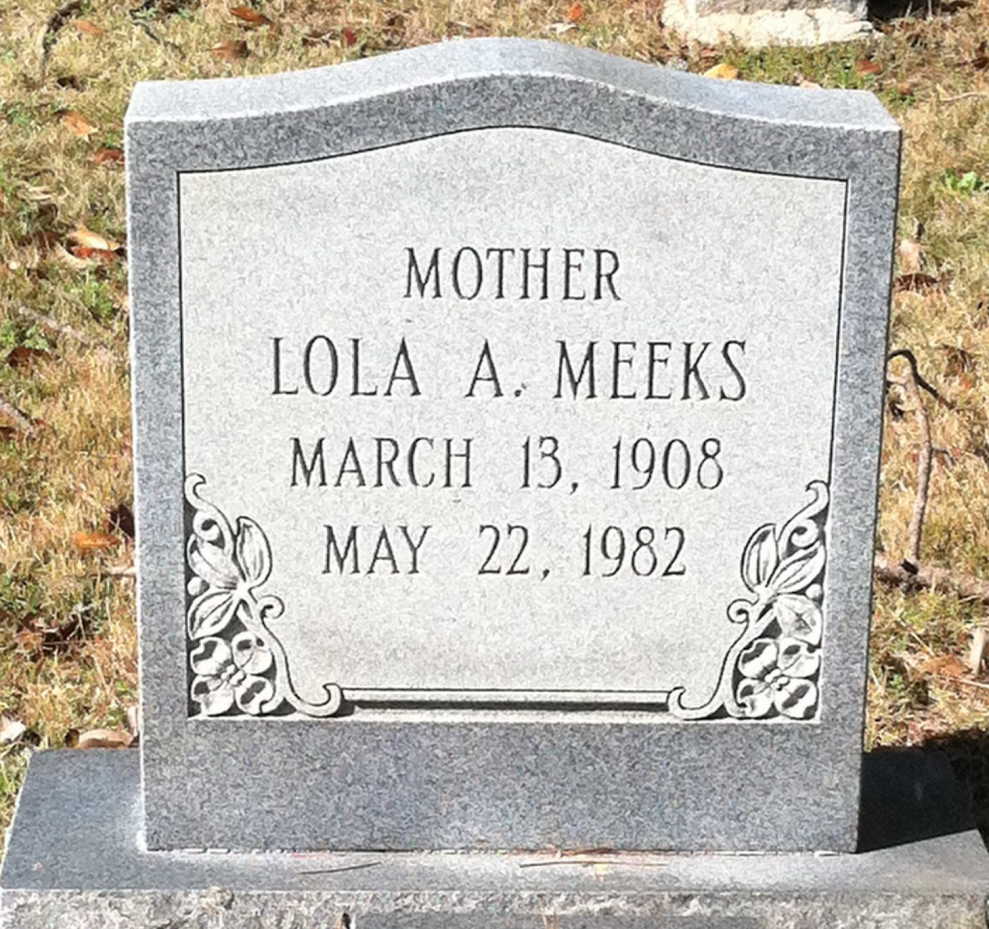

Wilson died in 1960. Bryant Sr. died in 1965. Lola Meeks died in 1982. With her, died the last living knowledge of her desperation to avoid being tracked down by her first ex-husband. As did the last first-hand account of the true nature of her relationship with her second ex-husband. But there is one of Lola’s relationships on which the historical record is perfectly clear. When Lola Alderman’s body was buried in her adopted home of Macon, Georgia in May of 1982, the epitaph on her headstone bore one word and one word alone: “Mother.”

In the spring of 1979, 47-year-old Bobby Bowden was hitting the booster circuit following his third season as the head coach at FSU. In May of that year, Bowden spoke at the Holiday Inn in Lido Beach, a barrier island just off Sarasota on Florida’s Gulf Coast. Sharing the stage with Bowden that day was 53-year-old Junior Meeks. Unlike Bowden, Meeks was not there in his capacity as a football star; after one year in the NFL and five coaching high school football, Meeks left that world behind to start his own business. That day in the Holiday Inn ballroom, Meeks was being recognized for raising $200,000 to fund the construction of a 12,000-square-foot health and fitness center at the Sarasota YMCA.

Four years earlier, the smart money would have been on the Sarasota Y closing its doors for good before it ever celebrated the construction of a new building. In 1975, the YMCA found itself $280,000 in debt, with revenue coming from just 400 dues-paying members. It was then that Meeks stepped in as chairman of the YMCA’s board of directors, overseeing a fundraising drive that paid off the organizations back taxes within 10 days; had they missed that deadline, the building would have been closed and put up for auction. The Tampa Tribune called the last-minute heroics a “goal line stand.”

But Meeks did far more than just gladhand wealthy benefactors. He was part of a group of a few-dozen volunteers who spent weekends restoring the YMCA’s dilapidated buildings. This included tasks as menial as getting down on hands and knees with a putty scraper to clear the floors of several layers of wax, which had accumulated through years of improper cleaning practices.

With the crisis averted, the next step was attracting new members. The building Meeks had helped raise money for in ‘79 was a cardiac therapy center. Then came a pre-school program, two new swimming pools, an aerobics studio, youth sports leagues, and a world-class gymnastics facility. By 1989, membership had swelled to 10,000 and the Sarasota Y had an operating budget of $2.7 million.

By the late 1980s, the Sarasota Y had became a pillar of its community. For that matter, it became a pillar of several other communities; members drove in from as far as 15 miles away, passing several other gyms — and sometimes passing other YMCAs. Expecting mothers in their second trimester joined waiting lists for the Y’s expanding portfolio of preschool programs.

“I’d place God first and then family and probably the business,” a Sarasota car dealer told the Tampa Tribune. “The YMCA would be next.”

But the YMCA’s revival was no match for the destabilizing forces in the 21st century economy. In 2019, declining membership forced the Sarasota YMCA to close down its fitness centers. A statement from the YMCA board said it would be “turning 100% of its focus to operating the YMCA’s ongoing foster care and social services programs that have served vulnerable populations in this community for many decades, including abused, neglected and at-risk children.”

Surely, this news would have been a grave disappointment to Meeks, who died in 2007. But he might have been glad to know that even after his death — even after the YMCA’s death — his efforts preserved a lifeline for children with troubled home lives.

For the kind of children who show up in the emergency room with scalp lacerations and dubious of accounts of accidentally head-butting a wall.