The human brain is not a computer

Don't make me tap the sign. Read to the end for two good sci-fi short stories and a trailblazing sci-fi movie from 1956.

People are not computers. The human brain is not a computer. This is one of My Things. It is so much one of My Things that I will sometimes go on tangents about it during job interviews, even knowing that I’m diminishing my chances of getting hired.

This is a high-paced job, and you’ll need to be able to multi-task. Will that be a problem?

“Well, to be honest I try to avoid multitasking whenever possible. The word ‘multi-tasking’ was actually invented to describe computers! But people are not computers, capable of running multiple applications at once with minimal performance loss. There’s clear scientific evidence that when humans try to do two things at the same time, what you actually end up with is having done two things rather poorly.”

For a human, to multi-task is to purposefully distract yourself from what you’re trying to accomplish and passing it off as “efficient” and “productive.” This seems so glaringly obvious that it honestly feels a bit silly to expend words pointing it out. Even if you try to tell me that human multi-tasking is more about switching between tasks rather than doing them simultaneously, the act of switching between tasks bears a very real cost!

And yet the computer has nevertheless become the dominant metaphor for describing human cognition.

Think about how many times in the past month someone told you whether or not they had the bandwidth to take on a project. Or how much the mythology of the “repressed memory” implicitly relies on the idea of a human mind with corrupted files capable of being debugged and restored.

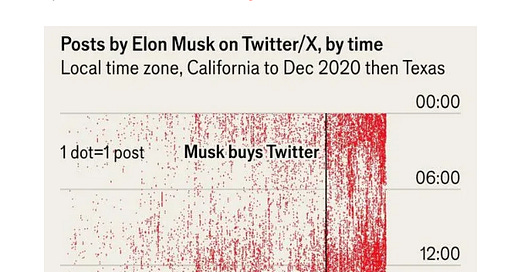

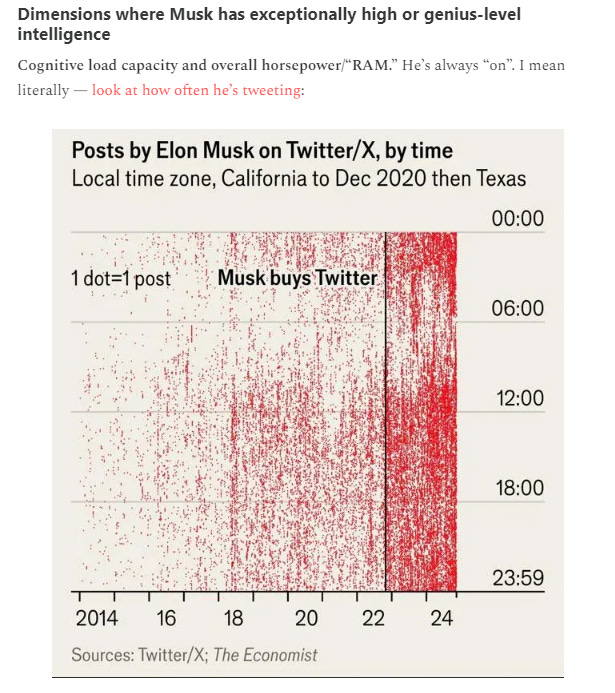

Or consider the bizarre jag Nate Silver took this week about how the frequency with which Elon Musk tweets is actually a demonstration of his genius.

Do I really have to say it again? The human brain is not a computer.

If you are spending that much time tweeting, then you are necessarily not spending it doing other things. Things like taking the time to find out whether or not the federal employees you’re firing are responsible for safeguarding America’s nuclear arsenal, fighting the bird flu, or unlocking the bathrooms at Yosemite National Park. Or bothering to find out whether tens of millions of dead people really are receiving Social Security before falsely claiming you’ve discovered that they are. Or bothering to find out what a pharmacy benefit manager is before single-handedly tanking a bi-partisan bill that would have saved Americans money on prescription drugs.

Elon Musk starts to make a lot more sense when you understand that, contrary to Nate Silver’s thesis, he’s not a breathtaking genius with misaligned morals. He’s just a ketamine-addicted trust-fund baby and a dilettante.

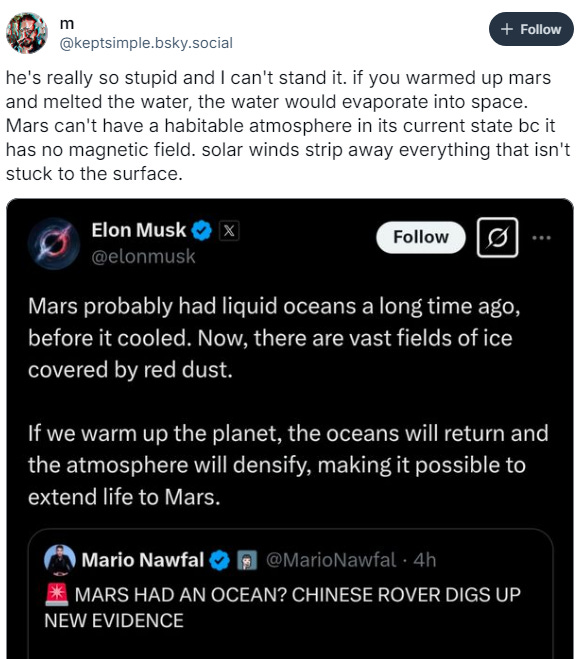

He’s even a complete dumbass about things he’s sunk billions of dollars into.

To me, Elon Musk is the logical end point of a society organized around the idea that the human brain is a computer. An entire planet of people with no skills, who aren’t experts on any one topic — but have looked many of them up on Wikipedia.

Two good sci-fi short stories

I’ve really been enjoying the Lost Sci-Fi podcast, wherein audiobook narrator Scott Miller reads old sf short-stories, largely drawing from the 1950s and 1960s. Miller is a talented and versatile voice actor, equally capable of giving life to stories that are on both the more whimsical end and the more ominous/sinister end of the sf spectrum. (And he’s got just a hint of a Southern drawl that changes my experience of listening to the stories in a way that I find interesting.)

Two episodes in particular really knocked me on my ass recently: The Man Who Could Work Miracles by H.G. Welles and The Hanging Stranger by Philip K. Dick. My sole previous exposure to H.G. Welles’ prose was The War of the Worlds, and I came away thinking the book was an interesting historical artifact but that I would nevertheless probably not be reading any more H.G. Welles. But after listening to Miracles, I owe H.G. Welles an apology: I was not familiar with your game.

Here’s a taste, from the story’s opening paragraph:

It is doubtful whether the gift was innate. For my own part, I think it came to him suddenly. Indeed, until he was thirty he was a sceptic, and did not believe in miraculous powers. And here, since it is the most convenient place, I must mention that he was a little man, and had eyes of a hot brown, very erect red hair, a moustache with ends that he twisted up, and freckles. His name was George McWhirter Fotheringay−−not the sort of name by any means to lead to any expectation of miracles−−and he was clerk at Gomshott's. He was greatly addicted to assertive argument. It was while he was asserting the impossibility of miracles that he had his first intimation of his extraordinary powers. This particular argument was being held in the bar of the Long Dragon, and Toddy Beamish was conducting the opposition by a monotonous but effective "So you say," that drove Mr. Fotheringay to the very limit of his patience.

I was in from the moment I found out the main character’s name was George McWhorter Fotheringay.

Unlike with Welles, I was already well-acquainted with Philip K. Dick’s chops, but I had not yet come across 1953’s The Hanging Stranger. I came away from the experience utterly gobsmacked.

From the lamppost something was hanging. A shapeless dark bundle, swinging a little with the wind. Like a dummy of some sort. Loyce rolled down his window and peered out. What the hell was it? A display of some kind? Sometimes the Chamber of Commerce put up displays in the square.

Again he made a U-turn and brought his car around. He passed the park and concentrated on the dark bundle. It wasn't a dummy. And if it was a display it was a strange kind. The hackles on his neck rose and he swallowed uneasily. Sweat slid out on his face and hands.

It was a body. A human body.

"Look at it!" Loyce snapped. "Come on out here!"

Don Fergusson came slowly out of the store, buttoning his pin-stripe coat with dignity. "This is a big deal, Ed. I can't just leave the guy standing there."

"See it?" Ed pointed into the gathering gloom. The lamppost jutted up against the sky—the post and the bundle swinging from it. "There it is. How the hell long has it been there?" His voice rose excitedly. "What's wrong with everybody? They just walk on past!"

Don Fergusson lit a cigarette slowly. "Take it easy, old man. There must be a good reason, or it wouldn't be there."

"A reason! What kind of a reason?"

Fergusson shrugged. "Like the time the Traffic Safety Council put that wrecked Buick there. Some sort of civic thing. How would I know?"

Jack Potter from the shoe shop joined them. "What's up, boys?"

"There's a body hanging from the lamppost," Loyce said. "I'm going to call the cops."

"They must know about it," Potter said. "Or otherwise it wouldn't be there."

As you may have already intuited, it’s an allegory for the infiltration of local governments by the second wave of the KKK as well a commentary on the Red Scare.

A good sci-fi movie

Let’s stay in the mid-1950s and recommend Forbidden Planet (1956). Come for Young Leslie Nielsen in a non-comedic role, stay for the groundbreaking score (the first fully electronic film score in a major motion picture) and to witness the groundwork being laid for basically every Star Trek away mission to a mysterious planet where all is not what it initially seems to be. If you can get past the horrendous sexism (a tall order, to be fair), I think you’ll come away quite stunned that we were capable of producing a pretty good sf story with excellent visual effects as early as 1956.

Among other things, it was nice to finally understand one of the lines from the opening credits of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Listen to the Strange Studies of Strange stories podcast. I think you will like it